Matrioshka Automata

The language overview page discusses how compose.mk is secretly a programming language, even though it's perfectly fine to think of it terms of a library or a tool.

More to the point though.. compose.mk is a matrioshka language, and maybe the first one that's actually intended to be useful.

For compose.mk, the "objects" are containers or container specs that might be inlined or external, and/or foreign code. The "rules" are tasks or task-groups. First-class support for these as primitives turns out to be especially useful for things like wrappers, tool-factories, and even app-factories as seen in the rest of the site documentation.

This page is about identifying a through-line for the more concrete work elsewhere, for those who prefer overviews that focus less on applications and more on theory, architecture, and patterns. If you want to take in a few simple and concrete matrioshka demos before you continue reading, see instead this index of demos.

Matrioshka Idiom Basics

Typically matrioshkas in compose.mk use a variation on the working definition from earlier, and they have the following structure:

- First phase: declares a set of runtimes

- Second phase: implement some tasks

- Third phase: maps tasks and/or task-groups onto runtimes

A runtime might be an image tag, or a container definition that's inlined or external, etc. A task might be a make-target, a group of targets, or a polyglot. Sometimes the second phase is optional and we skip straight to phase 3. (For an example of that, see the declarative style for low-config TUIs with no need for target bodies.)

Using basic container dispatch idioms with external files is matrioshka-like, and almost all of the polyglot demos are very simple matrioshkas that define (or just mention) a runtime & execute foreign code there.

More involved matrioshkas usually have inlined containers or data, and they come in a few distinct categories that all have individual demos:

- Inlined Dockerfiles

- Extending inlined Dockerfiles

- Inlined compose files

- Passing inlined data structures

Has Science Gone Too Far?

Any place you can use embedded stuff with compose.mk is a special case, and nothing prevents you from using an external file. But a determined individual can make a mess of anything so it's probably worth pointing out that there are reasons for matrioshka-dolling that aren't totally insane.

Here's a few arguments that suggest matrioshka-dolling has some legitimate use-cases:

- Since tool containers tend to be small and change infrequently, being self-contained reduces change-related friction that you usually get with external files, external repositories, and external registries.

- Sometimes having nested containers or data is just a way of keeping demos/prototypes tight and small, because being self-contained is the most legible or instructive.

- Being self-contained is also at least correlated with other nice things like stability and reproducibility.

- Matrioshkas are actually a pretty good format for a bug reports / minimum reproducible examples.

- Matrioshkas are also a good format for test-cases of some distributed systems. 2

Whether we're talking about bug reports, test-cases, or tutorials.. matrioshka's can help make things "batteries included" in the sense that they are actually executable, rather than a series of instructions asking you manually copy/paste a bunch of stuff in different files to get a test-harness going.

The rest of this page develops more interesting arguments in terms of fancy stuff like patterns, idioms, and metalanguages but the simple justifications above are actually very practical. Just don't be antisocial by embedding a gnarly and frequently-changing 300-line Dockerfile into your team's Makefile, and you'll be fine ;)

See the design philosophy docs for a more detailed long-format dicussion of this type of thing.

Matrioshka-Bridge Pattern

The previous section on idiom basics links several demos that focus on inlining or "embedding" containers and data. A more interesting topic is the kind of bridge-building projects that you can see in the ansible demo and the the justfile demo.

Both of these demos are instances of a general pattern that goes like this:

- Describe a foreign toolchain. (e.g. image tags, container definitions inlined or external, etc)

- Drill a tiny hole through the matrioshka layers, exposing or "lifting" something useful by abstracting away the fact that the task actually happens in a container.

- Better yet, lift something useful that is parametric and then you have a bridge.

- Combine bridges at the level of

compose.mkto easily express ideas across systems. - Compose bridges or groups of bridges, using

fluxfor workflows,tuxfor TUIs, etc.

If you don't need to combine systems, you can actually stop after step 3, and you have something like a "tool factory", where you can wrap the interface of something else and potentially change it. Summarizing the ansible demo, we lifted ansible's whole adhoc feature up out of the container, making it available to the host that doesn't have Ansible. We also exposed and actually changed the default interface, insisting on JSON, providing aliased entrypoints for common use-cases, etc. By using compose.mk's support for packaging/compilation it's even more obvious that you can spin off this whole effort as a stand-alone tool, or several tools. This is an example of using the matrioshka-bridge pattern to create a tool factory.

By the time you get to step 4, the possibilities for composition are surprisingly powerful, expressive, and flexible, in large part because the homoiconicity we discussed earlier starts to pay off. Summarizing the justfile demo, embedding a justfile is incidental since we could easily work with an external one, but again the interesting part again is a bridge across layers. We lift part of the just interface, then besides changing/exposing that interface, we actually wrapped it and compose our way to new functionality. As a result.. we end up with an interactive task selector in just one line.

Step 5 is where the real magic happens, and the demos mentioned so far are just hints. Demonstrating the potential for this seriously under realistic circumstances starts to want more tools and larger use-cases.. which is a challenge for brief examples. See the platforming demo for a sketch, or the notebooking demo. See also a preview of the sister project @ k8s-tools2, which uses compose.mk to automate cluster-lifecycles for complex orchestration across a bigger toolbox.

Advanced Matrioshka Idioms

In the previous sections, we've looked at demos, idioms and patterns at differently levels of complexity. But some people might wonder.. is this really significantly different than say, heredocs[^1] or random docker sdk's in whatever language?

The answer is yes!, because besides better options for structuring code and attempting to treat containers as "first class" objects, compose.mk is also fluent about data and control flow across layers.

As one example, stage stacks allow targets to represent operations on shared datastructures, and this is one one way to accomplish message-passing across matrioshka layers.

Since compose.mk tool-container invocations default to volume-mounts for the working directory and the docker socket automatically, things like structured io can work reliably anywhere. One consequence of this is a kind of "late binding" style, where basically you don't necessarily have to think much about whether tasks run on the host, or run on containers.

Related Links

See the demos for Embedded Containers & Data and the collection of Polyglot Demos, which are all matrioshkas to some extent.

For an extreme example of "fluency" across matrioshka layers, check out the makeception demo, where we use compose.mk to embed 2 container definitions and to build and steer them. The build process itself is encapsulated inside the same file: rather than monolithic top-to-bottom bash in the Dockerfile, provisioning tasks can be expressed as normal targets which are executed as usual, may call other targets, etc.

For an advanced example in service of a more conventional use-case, you might want to take a look at the Notebooking Demo, which uses 3 different containers (a formal-methods toolkit) to augment the behaviour of a 4th container (a jupyter lab server).")

References

[^1] via the esolangs wiki

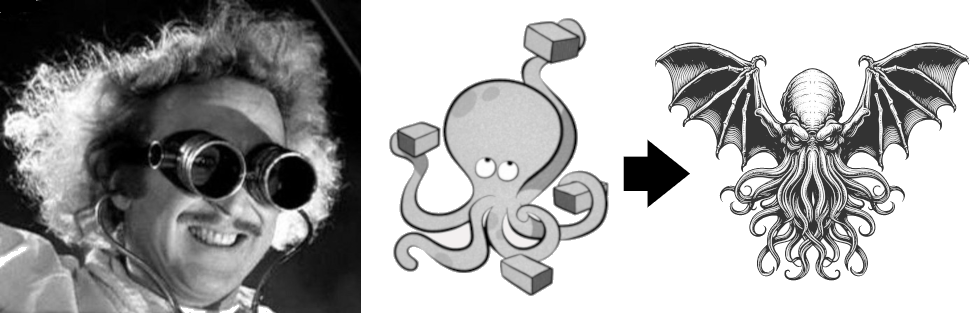

Matrioshka Language

Matrioshka languages can be identified by their program forms, which will have multiple, distinct 'phases' with different syntactic and semantic rules. There are often two phases; the first gives a set of rules, and the second provides objects on which those rules are to be applied.[^1]